Cheese and history.

it is an article by Formaggio.it – formaggio.it

A few years ago Italians were asked what should never be lacking in their refrigerators. The most popular answer was: cheese.

What do the cheese is?

It is nature and life.

The cheese is made only with milk or milk cream, any label that does not report these two raw materials, alone or together, does not indicate a cheese.

Beyond the consumer satisfaction, however, let’s see in detail what cheese is. It is above all an exceptional food, from all points of view.

Moreover, it is the territorial food par excellence, there is no place in Italy that does not have its typical cheese. The link with the land is so deeply rooted that the consumer is the first supporter, in many ways, of the local cheese.

In reality it is the physical and chemical composition of the cheese that makes it a complete dish, so much so that it is included in many diets.

What says with certainty what cheese is, however, is only the definition given by the legislator of Article 32, of the R.D.L. 10/15/25: “The name of cheese or cheese is intended for the product obtained from whole milk, partially or totally skimmed, or from the cream, following acid or rennet coagulation, also using ferments and salt from kitchen “. In our opinion, this is a very clear definition. The cheese, in fact, is made only with milk or cream, any label that does not report these two raw materials, alone or together, does not indicate a cheese. The milk can be used whole or skimmed, raw or pasteurized, inoculated or not with natural or selected milk enzymes, which are the life of the original milk and the cheese produced. The latter is such a vital product that sometimes to make it just drive the milk in its natural fermentation. He does everything by himself. And give us something wonderful.

Lost in time

The most recent discovery is traces of cheese on a mummy found in the north-western part of China dating back to 1615 BC.

Let’s start with the legend, because a bit of “color” is always good. The legend, in fact, tells that an Arab merchant, crossing the desert, brought with him, as a dish, the milk contained in a bag made from the stomach of a sheep. The heat, the enzymes of the bag and the action of the movement acidified the milk turning it into “cheese”.

Milk, enzymes, movement, acidification: there is a link.

According to the official history, brings up the ancient Greeks. Yeah, we’ve to start from they. To discover the origins of the etymology of the word “cheese”. It derives, in fact, from “formos”, a term used to indicate the basket where the curdled milk was deposited to give it shape. The “formos” then became the “form” of the Romans, then the “fromage” of the French, to get to the very Italian “cheese”.

As for the birth of cheese, however, the way to say “lost in time”, it’s spot on.

The oldest cheese in the world

However, there is an objective, and even rather recent, comparison dated 2014.

The oldest cheese in the world, in fact, was found on the chest and neck of a mummy found in the northwestern part of China (in the Taklamakan desert) dating back to 1615 BC. These were the typical offers made by the living to the dead for the journey in the afterlife. The lumps of cheese were found preserved in an almost hermetic environment on the bodies of 10 mysterious mummies of the Bronze Age. The analysis of the finds revealed that it was a lactic coagulation cheese, transformed without the use of rennet, but thanks to the action of yeasts, in many ways related to kefir, derived from milk that would have Caucasian origins . Furthermore, analyzes revealed that the cheese had a low salt content and that this could be used for local consumption.

First farming traces

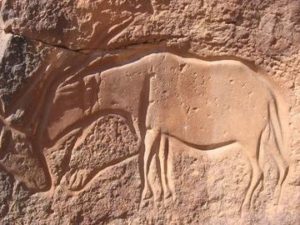

First traces of sheep and goat breeding were found in Asia and date back to 7,000- 6000 BC.

With pastoralism, man’s food resources derived from meat and milk. The latter deteriorated. An unknown emerit one day brightened up noticing that the milk, left for some time in some containers, spontaneously coagulated if fig latex was added. Following this process the solid part was divided into a liquid part (whey) and a paste (curd) which increased in consistency until it took the shape of the container.

The acidification by microbial microflora, therefore, is certainly the first transformation of milk practiced in ancient times. It was nothing but the easiest way to “preserve” in its solid form a liquid and perishable raw material.

From the Bible to Homer

From here started also the production of soft cheese, consumed exclusively fresh. Incredible, but true. Already in those remote times we were confronted with digestibility.

The milk cause problems (confirmation of the deficiency of the enzyme lactase in the human species), while the cheese was easier to digest. Game, then, immediately won by the latter.

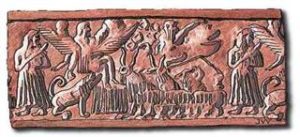

The oldest document confirming the practice of making cheese from milk dates back to findings of Mesopotamian origin dated III millennium BC. These are the first documents that show the processing stages of the cheese, in particular the “Frieze of the Dairy”, a Sumerian bas-relief representing the priests in the milking operation.

Testimonies of the use of cheese are found throughout the ancient world: in Europe, in Africa, and in Asia.

The sources? very authoritative: the Bible and Homer (in the Odyssey, Polyphemus prepared cheese), but also Hippocrates, who in the fourth century BC talk about the healthy characteristics of the cheese; Aristotle, for his part, first describes the method for obtaining cheese from the fig coagulant.

The Romans and the seasoning

In such a compelling story, however, mythology can not be missing. Which traces the use of cheese to Aristeo, son of Apollo and the nymph Cyrene. The latter would teach men the art of cheese, in addition to that of pastoralism and beekeeping.

Always the mythology, brings into play also Amaltea, the nurse of Jupiter, owner of a celebrated Cretan goat.

As for its energy value, however, the cheese was considered a food particularly suitable for athletes who competed at the Olympics.

Even the Romans were producers and consumers of cheese. In addition to sheep’s milk, they also began to use cow’s milk (rarely used by their predecessors, since they were considered harmful) and learned how to season them. A sort of first classification comes from Marco Terenzio Varrone illustrating the main types of cheeses consumed in the 2nd century BC. (fresh and seasoned cow, goat and sheep) and in De rustica documents how the taste of the age was aimed at cheeses obtained with hare or goat rennet instead of lamb.

And the Etruscans? They used to perfecting the use of vegetable type coagulants, such as thistle flower and fig milk, and their application techniques. Those of lamb or kid, however, met more.

The Romans, also used to use saffron and vinegar. Moreover, to accelerate the seasoning of the cheeses they put them under pressure by pressing with big stones. Real dairy art, therefore. Which spread in the conquered lands. It dates back to 58 A.D. the first cheese produced in Switzerland, as reported by Pliny the Elder, who speaks of the Helvetic tribe. The English, however, arrived later. It will be necessary to wait for 120 A.D., under the empire of Hadrian.

Carlo Magno, tra “passione” e dicerie

La prima parte del Medioevo fu un periodo conflittuale per il formaggio. Generato da pregiudizi. Gli ignoti meccanismi di coagulazione e fermentazione, difatti, erano visti con sospetto e i trattati di dietetica ne limitavano il consumo, in quanto si riteneva che solo piccole dosi di formaggio non nuocessero alla salute.

Il Basso Medioevo fece giustizia al riguardo. Se in un primo momento il formaggio era considerato il cibo dei poveri, in quel lasso di tempo venne rivalutato, in quanto pietanza sostitutiva della carne nei giorni di astinenza infrasettimanale, di Vigilia e Quaresima.

Le fonti autorevoli del Medioevo sono giocoforza quelle dei monaci e delle abbazie dove il formaggio veniva prodotto e consumato. I monasteri diedero un importante impulso alla produzione casearia. Nell’ambito delle loro attività economico-rurali, allevavano bovini stanziali. Pratica che permise la nascita di nuove varietà di formaggio.

In una biografia di Carlo Magno risalente al IX secolo, si racconta di una visita, per la verità un po’ a sorpresa, dell’imperatore a un importante vescovo. L’imperatore, inatteso, aveva scelto un giorno di astinenza dalle carni e allora il vescovo, non disponendo di pesce per onorare l’illustre commensale, servì un semplice pasto che diede modo a Carlo di gustare quello che lui definì “un ottimo formaggio bianco e grasso”. Fece talmente breccia nel suo nel cuore che arrivò ad ordinarne due casse l’anno.

Attenzione, però. Sul rapporto fra Carlo Magno e il formaggio le dicerie popolari si sprecano. Eginardo, ad esempio, descrive la perplessità dell’imperatore di fronte a una fetta di Gorgonzola. Mentre c’è chi giura che il nome della varietà Castelmagno (oggi una D.O.P.) deriva dal fatto che il sovrano ne era ghiotto… I periodi non coincidono, ma la storiella è suggestiva.

Da cibo “povero” alle tavole “nobili”

Le testimonianze sulla diffusione del formaggio nelle tavolate “nobili” iniziano a comparire tra il tardo Duecento e il Quattrocento nei ricettari di cucina.

Inizialmente come ingrediente di vivande elaborate, in seguito con peso maggiore. Tanto da essere servito come pietanza alla mensa dei papi e ai matrimoni della famiglia de Medici e degli Estensi, che offrivano abbondanti bocconi di Parmigiano.

Le tariffe dei pedaggi e le gabelle imperanti comprovano che, a partire almeno dal secolo XIII, formaggi di qualità differenti circolavano sulle strade d’Italia e, attraverso valichi alpini, raggiungevano spesso mercati molto lontani dalle zone d’origine. In quei secoli in Italia i formaggi più diffusi erano fondamentalmente due: il Marzolino, di origine toscana, chiamato così perché prodotto a marzo, e il Parmigiano, delle regioni cisalpine, detto anche “maggengo”, perché prodotto in maggio.

Finché i monaci si scatenarono. A partire dal XII secolo proprio nelle Abbazie di Moggio Udinese, Chiaravalle, San Lorenzo di Capua, nacquero il Montasio, il Grana e la Mozzarella di bufala.

E via tante altre tipologie diventate col tempo patrimonio dell’alimentare italiano.

Dai nascondigli, ecco i formaggi di fossa

Il formaggio di fossa merita due righe a parte. Secondo la leggenda, pare che la sua origine risalga al 1486, quando Alfonso d’Aragona, figlio del re di Napoli, reduce da una pesante sconfitta operata dai francesi, ottenne ospitalità da Girolamo Riario, Signore di Forlì.

To supply and feed their needings, Alfonso of Aragon with his troops began to plunder the peasants of the surrounding areas of Forlí. Peasants, to defend themselves, start to hiding supplies in sandstone pits. When, in November, the soldiers left and there were no more risks of raids, the peasants unearthed their supplies. They expected to find moldy cheese. Instead they found some cheese that had changed its organoleptic characteristics, acquiring an excellent aroma.

Thus, by luck, one of the most delicious gastronomic rarities of Romagna and Marche was discovered.

Lascia un commento